Maps of Ukraine

You got lost in the ongoing (media) war between Russia and Ukraine? We have selected ten old maps from the Royal Library of Belgium (KBR) cartographic collection illustrating the gepolitical history of what is now Ukraine. They offer you a glimpse of the region’s complex past as a borderland. Although not exhaustive, the selection of maps chronologically ordered from the sixteenth to the twentieth century illustrates some of the country’s politically significant dates. The descriptive notes that accompany each of the images are intended to arouse your curiosity and will to look further into the maps. Beware though, maps are never neutral, and often serve a political agenda.

An excellent reading companion could be S. Seegel, Mapping Europe’s Borderlands. Russian Cartography in the Age of Empire, Chicago-London, The University of Chicago Press, 2012.

All reproduced documents are published under KBR Copyright.

Humanistic cartography

![Taurica Chersonesus nostra aetate Przecopsca et Gazara dicitur […]](/uploads/images/1.BE-KBR00_B-16374889_0000-00-00_00_0001_result.jpg)

KBR, XIV Ukraine - (1638) - Mercator - IV 9696

Gerard Mercator (1512-1594) is renowned for his atlas, which already includes this map. The toponym Taurica Chersonesus refers to the Greek colony Chersonesos (which is Greek for peninsula) in Taurica, today the Crimea. The region on the mainland that borders on the peninsula bears the same name. The toponym Tartaria Przecopensis is also used. It refers to the city of Perekop right in the north of the Crimea where the peninsula touches the mainland. As a gateway to the peninsula, Perekop has a strategic location. Fortified by the Greek and Tatars, it became a Genovese colony in the 15th century. Many Italian merchants travelled to the area in the 15th and 16th century which accounts for the large number of Italian toponyms on the map. Most notable is the Italian word for the Sea of Azov on the map, Mare delle zabache, a name used by Venetians and Genoese in the Middle Ages. It is thought to have derived from the name Sivaschi, today Sivas, a shallow lake with a high salinity in the northeast of the Crimea, not far from Perekop. In 1783, Perekop and the remainder of the Crimea became Russian. The region was the theatre of a true world war in the middle of the 19th century but remained Russian. In 1954 the Crimea was transferred to Ukraine. It was occupied by Russia in 2014.

The name Tartaria refers to the old late medieval empire of the Golden Horde. It was populated by Mongolians and Turkish and is better known in historiography as the Crimean Khanate. On the verso of this edition, Mercator explores this - to him more recent - history of the region.

We can fairly easily recognize the name of Kyiv in the toponym Kioff on the map. The city was then still a part of Lithuania. The lands on the other side of the Dnieper were already Russian. Podolia, located between the Dniester (Tyras) and the Southern Bug (Bog on the map in line with the Sinyuka/Szinouoda), today largely Ukrainian, is depicted here as an independent area. It was conquered by Lithuania from the Golden Horde in the 14th century, and belonged as of 1569 (Union of Lublin) to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The map was first published in 1595, it was reprinted several times and was ‘modernized’ in the years 1630, but the map image was not substantially altered. The Amsterdam publisher Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571-1638) published a copy of the map which has the border of Lithuania moved more to the east. This eastward shift can be partially explained by the strongly changed depiction of the course of the Dnieper.

Sources: Gerard Mercator Cartograaf 1512-1594, Brussel, Koninklijke bibliotheek Albert I, 1994 ; P. van Gestel et alii, Maps in Books of Russia and Polen Published in the Netherlands to 1800, Houten, Hes & De Graaf, 2011.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

![Le royaume de Pologne comprenant les Etats de Pologne et de Lithuanie, […]](/uploads/images/2.BE-KBR00_B-16669446_0000-00-00_00_0001_result.jpg)

KBR, XIV Pologne - 1691 - Tillemont - III 9676

Jean-Baptiste Nolin (ca 1657-1708) was a French engraver who came to publish maps himself through his collaboration with Vincenzo Coronelli. His publishing house was based in Paris and also carried out assignments for Louis XIV. This map of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth dates from the time Nolin teamed up with the Italian cartographer and globe maker, but would be reprinted until well into the 18th century.

The Commonwealth was the result of the merging of the personal union of both principalities into one single state with the Union of Lublin in 1569. It remained an important European player until 1795 when Poland was eventually divided among Prussia, Austria and Russia. Multi-ethnic and multi-religious, the Commonwealth evolved from a state with a great tolerance and dynamic culture to a state in which the catholic part of the population became increasingly dominant.

The map is based on the work of Szymon Starowolski and Christoph Hartknoch among others. Starowolski, Starovolscius in Latin (1588 - 1656), was a known prolific writer and historian from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. He published most of his books in Latin, like his biography of Sigismund I of Poland (1467-1548) who was also Grand Duke of Lithuania. Under the reign of his successor, Sigismund II Augustus (1520-1572), both principalities would unite in one state. Being a firm Catholic – he would be ordained a priest later in life – Starowolski was the spokesperson of the rise in religious intolerance in his country. On the other hand, the Prussian native Christoph Hartknoch (1644-1687) was a Protestant. He was a famous historian of the Commonwealth. His historiographical work was and is a major source for the history of Prussia, Pomerania, Lower Lithuania, Courland and Poland.

In the upper left, the map shows the administrative and religious (catholic) division of the Polish Kingdom and of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania according to Jean-Nicholas de Tralage, Sieur de Tillemon. De Tralage (1640-1720) was a geographer, cartographer and historian, as well as an important print collector.

On the map, we find the voivodeships of Kyiv and Bratslav, and the eastern part of Lithuania, which together form ‘la Petite Russie’. This is the name that was used at the time in the Russian Empire to designate the northern part of present-day Ukraine. It finds its origin in the name given by the Byzantines to the area within the context of the organization of the Orthodox Church. It is derived from the term Rus, that refers to the old, medieval principality of Kyiv, from which derives the toponym Ruthenia.

Sources: Starovolsci Respublica Polonica, duobus libris illustrata: qvorum prior, historiæ Polonicæ memorabiliora ..., posterior vero jus publicum Reipublicæ Polonicæ, Lithvanicæ ... comprehendit. His adjecta est dissertatio historica De originibus Pomeranicis (1678) https://books.google.be/books?id=Eq_igAnAT_0C&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_atb&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false; M. Sponberg-Pedley, The Commerce of Cartography: Making and Marketing Maps in Eighteenth-Century France and England, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2005.

18th-century Ukraine

![Amplissima Ucraniae regio, palatinatus Kioviensem et Braclaviensem complectens, cum […]](/uploads/images/3.BE-KBR00_B-18247070_0000-00-00_00_0001_result.jpg)

KBR, XIV Ukraine - (1757-) - Lotter - III 10321

Lotter Tobias Conrad (1717-1777) from Augsburg, son-in-law of the printer and publisher Matthäus Seutter (1678-1757), printed this map of the Ukrainian region around 1757. As the title informs us, the map gives a depiction of the geopolitical situation at the time. Ukraine is the region that encompasses the voivodeships of Kyiv and Bratslav. A voivodeship is an administrative division typical of Poland, which was originally governed by a voivode or army commander. One can compare it to what we call a duchy. On this map the term is translated into Latin as Palatinatus. Both voivodeships belonged to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1569 (the Union of Lublin) to 1793 – although in 1668 Kyiv and left-bank Ukraine (the part of Ukraine on the east bank of the Dnieper River) were handed over to Russia under the Treaty of Andrusovo (1667). Prior to that they were part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Together with the voivodeship of Podole, the voivodeship of Bratslav which is also called the Ukrainian Podolia, formed the historic province of Podolia. At the end of the 18th century, with the Second Partition of Poland in 1793, both would be incorporated into the Russian Empire. The ornamental borders of the cartouche refer to the agricultural character of the region, which is to the present day known as the granary of the neighbouring countries.

Sources: Ritter, Michael. "Probst and Lotter: An Eighteenth-Century Map Publishing House in Germany". Imago Mundi. 53 (2001): 130-135 https://www.jstor.org/stable/1151567; Shiyan, Roman I. “The ‘Rumour of Betrayal’ and the 1668 Anti-Russian Uprising in Left-Bank Ukraine.” Canadian Slavonic Papers / Revue Canadienne Des Slavistes 53, no. 2/4 (2011): 245–70 http://www.jstor.org/stable/41708341.

Turks and Ta(r)tars

![Theatrum belli Russorum victoriis illustratum sive Nova et […]](/uploads/images/4.BE-KBR00_B-18242333_0000-00-00_00_0001_result.jpg)

KBR, XIV Ukraine - (1757-) - Lotter - III 12713

Lotter Tobias Conrad (1717-1777) from Augsburg is the publisher of this map of the Ukrainian region. This edition dates from after 1757. As the title states, it is an exact depiction of the Turkish and Tatarian territories between the Niester and the Danube, and in the Crimea. This area is – still according to the title – the theatre of the war which was won by the Russians.

When we take a closer look at the map, we see a picture that is somewhat different. The focus of the map is on the area around Kyiv, Bratslav and the Crimea. The colouration tells us about the political divisions in the war zone: Kyiv and left-bank Ukraine, both Russian as of 1668, are rendered in the same lemon yellow shade, with the exception of the region of Lubny. But the Bratslav voivodeship, that then still belonged to the Commonwealth, is also rendered in this yellowish colour, as is the Zaporozhian Sich, the semi-autonomous state of Cossacks in Central and Eastern Ukraine. They form as it were a Polish-Russian alliance against the Tatars that populate the area at the mouth of the Niester and east of the Dnieper River - Tartaria oczacoviensis in green and Tartaria Minor in pink. The Tatars also make an appearance in both cartouches: at the lower right we see an armed Tatar next to a Turkish soldier, at the upper left the Tatars have been taken prisoner by a Roman looking warrior. The last cartouche shows Lady Justice who is pictured in an effort to justify the war. Her foot rests on the chains of one of the captured Tatars. Standing behind her is Fame.

But which are these Russian victories that are mentioned in the title? It is an allusion to the seizing of the Crimea by the Russians during the Russo-Turkish war of 1735-1739. In this war, Russia wanted to force a passage to the Black Sea and put an end to the looting committed by the Crimean Tatars who had the support of the Ottoman Empire. On this map, Tatars and Turkish are considered one and the same.

Finally, the printing plate that was used by Lotter came from his father-in-law Matthäus Seutter, who had engraved it for his Atlas novus of 1739.

Sources: Ritter, Michael. "Probst and Lotter: An Eighteenth-Century Map Publishing House in Germany". Imago Mundi. 53 (2001): 130-135 https://www.jstor.org/stable/1151567; Shiyan, Roman I. “The ‘Rumour of Betrayal’ and the 1668 Anti-Russian Uprising in Left-Bank Ukraine.” Canadian Slavonic Papers / Revue Canadienne Des Slavistes 53, no. 2/4 (2011): 245–70 http://www.jstor.org/stable/41708341.

The Russian Empire

![Carte des environs de la Mer-Noire où se trouvent l'Ukrayne, la Petite Tartarie, la Circassie, la Georgie, et […]](/uploads/images/5.BE-KBR00_B-18128147_0000-00-00_00_0001_result.jpg)

KBR, XIV Ukraine - 1783 - Delamarche - III 14774

The map is the work of the French geographer Robert de Vaugondy (1688-1766) and his son Didier (1723-1786). Their maps were known for their geographical accuracy. They were reprinted until well into the 19th century and in some cases modernized. An earlier edition of this map dates from 1769 and was probably made against the background of the war between Russians and Crimean Tatars over the Wild Fields, that appear as Loca deserta in Latin on many maps. This was the land north of the Black Sea that covers grosso modo the south of Ukraine. At that time, Catherine the Great (1729-1796) reigned over the Russian Empire. It was she who not only gained control of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth but ultimately even annexed large parts of it.

The cartouche notifies us that the map was improved for the purpose of the military operations that went on at the time, which is a reference to the Russo-Turkish war in the last quarter of the 18th century. In the year 1783, the date on the map, the Crimea, here coloured in rose, was permanently conquered by Russia from the Ottoman Empire. In 1787 the Empress even went on a tour of inspection across the Crimea.

The rose-yellow line on the map still marks the old border between the Ottoman and Russian Empire. Under Ottoman rule the Tatars, south of this line, enjoyed a certain degree of independence.

The copy that is shown here was published by Charles François Delamarche (1740-1817). In 1786 he bought the complete stock of Vaugondy maps, which means that this map was published after that date. The map’s dedicatee has not been changed, though ; it still is the duke of Choiseul, Étienne-François de Choiseul-Beaupré-Stainville (1719-1785), although he had died in 1785 and had already fallen out of grace with the king of France in 1770. It is his coat-of-arms that adorns the top part of the cartouche. He was Secretary of State for War from 1761 to 1770.

Sources: M. Sponberg Pedley, Bel et utiles. The work of the Robert de Vaugondy Family of Mapmakers, Tring, Map Collector Publications, 1992.

40 governorates

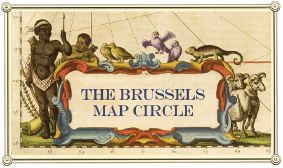

KBR, XIV Russie - (ca 1840) - Liechtenstern - III 13827

This map shows the European part of Russia in the first half of the 19th century. The 40 governments or provinces (goebernija) of the Russian Empire have each received a number. On the top left we find the glossary. Number 27 points to Ukraine which is then a part of Little Russia. The present-day Ukraine covers several numbers or provinces, including 23, 26, 27, 29, 30, 31, 37, 38, 40.

Theodor Freiherr von Liechtenstern (1799-1848) was an important figure in the development of educational cartography in the 19th century and an advocate for physical atlases. Not surprisingly, he taught geography in the cadet school of the Prussian army. His interest in physical cartography transpires in the representation of relief on this lithographic map. A special scale on the bottom left helps us understand the black and white shades on the map. For these hachures, von Liechtenstern made use of the model developed by general von Müffling (1775-1851).

The map is dated at around 1840, but it may be considerably older. An older version did exist, as it was discussed in detail in the Kritischer Wegweiser im Gebiete der Landkarten-Kunde (1829) by H. K. W. Berghaus (1797-1848), who himself was a prominent geographer, cartographer and author of a Physikalischer Atlas. The reviewer criticizes the ‘overimaginative’ representation of the Ural Mountains and the Caucasus, caused by the lack of knowledge at the time of these mountain ranges. The country’s subdivisions also appear to be inaccurate. A second reviewer suggests that a colouring of the provincial boundaries on the map would greatly improve its readability. The toponymy could also have been richer, according to the critic.

Sources: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodor_von_Liechtenstern; Heinrich Karl Wilhelm Berghaus, Nachrichten zur Beförderung der mathematisch-physikalischen Geographie und Hydrographie. Erster Band, Volume 7, Schropp & Comp., 1829 https://books.google.be/books?id=V9leAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

The Russo-Ottoman War

![[Map of post offices in the Russian Empire] / Il'in, Alexis Afinogenovich.](/uploads/images/7.BE-KBR00_B-18275752_1_result.jpg)

KBR, XIV Russie gén. - 1878 - Postes - III 10335

Alexey Afinogenovich Ilyin (1832-1889) was a Russian officer and publisher of maps. In 1859 he and his collegue Vladmir Poltoratsky (1830-1886) founded the company ‘chromolithography by Poltoratsky, Ilyin and Co.’ in Saint Petersburg. When Poltoratsky left the city in 1864, the firm changed its name to ‘A. Ilyin’s cartographic establishment’. Throughout his life, Ilyin was the cartographer of the Military Topographic Depot in Saint Petersburg. After his death the company was run by his sons. It was nationalized in 1918. The company, which not only published maps but also other publications such as school books, was a key player in the Great Reforms that were carried out by Tsar Alexander II in the years 1860-1870 and had the ambition to turn the Russian Empire into a modern European superpower.

The map shows the distribution of post offices in the Russian Empire. The distances between the offices are indicated. The post was delivered by horse at the time, and both horse and rider had to be relieved at regular intervals, which explains the large number of offices.

In the last quarter of the 19th century the Russian Empire consisted of – next to Russia itself – present-day Ukraine and Moldavia, Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan to the south, and Finland, the Baltic states and a part of present-day Poland, the Congress Poland which was created in 1815, to the north.

It is an interesting map because it shows the borders of the Russian Empire after the Russo-Ottoman war (1877-1878). The provinces Kars and Batumi in the Caucasus now lie within the borders of the Russian Empire, and the Budjak region (today spread over Ukraine and Moldavia) has been annexed by the Empire as well. Batumi and the Budjak region are well provided with post offices, Kars clearly is not. Additionally, we see the borders of the neighbouring countries west of the Russian Empire as defined at the Congress of Berlin (13 June - 13 July 1878). They are indicated by a black dash-dotted line : we distinguish from north to south consecutively Romania with to the east, bordering on the Black Sea, the Dobruja region (which is today part Romanian, part Bulgarian), Bulgaria, Eastern Rumelia and the Ottoman Empire. The Congress of Berlin toned down the three month old peace treaty between Russians and Ottomans, which was named after the village of San Stefano close to present-day Istanbul, to where the Russian army had advanced. This treaty had created an independent principality Bulgaria that also included Eastern Rumelia. The Congress of Berlin was called together by Germany to negotiate between the Russian Empire on the one hand, and Austria-Hungary and the United Kingdom on the other hand, all of whom were involved in the struggle for power in the Balkans and the Mediterranean. The borders were redrawn as a result. Bulgary lost Eastern Rumelia which was given back to the Ottoman Empire, Austria-Hungary gained Bosnia, the United Kingdom gained Cyprus. By way of compensation Russia was given the Caucasus.

Sources: http://expositions.nlr.ru/eng/map_ilyin; S. Seegel, Mapping Europe’s Borderlands. Russian Cartography in the Age of Empire, Chicago-London, The University of Chicago Press, 2012.

A Linguistic point of view

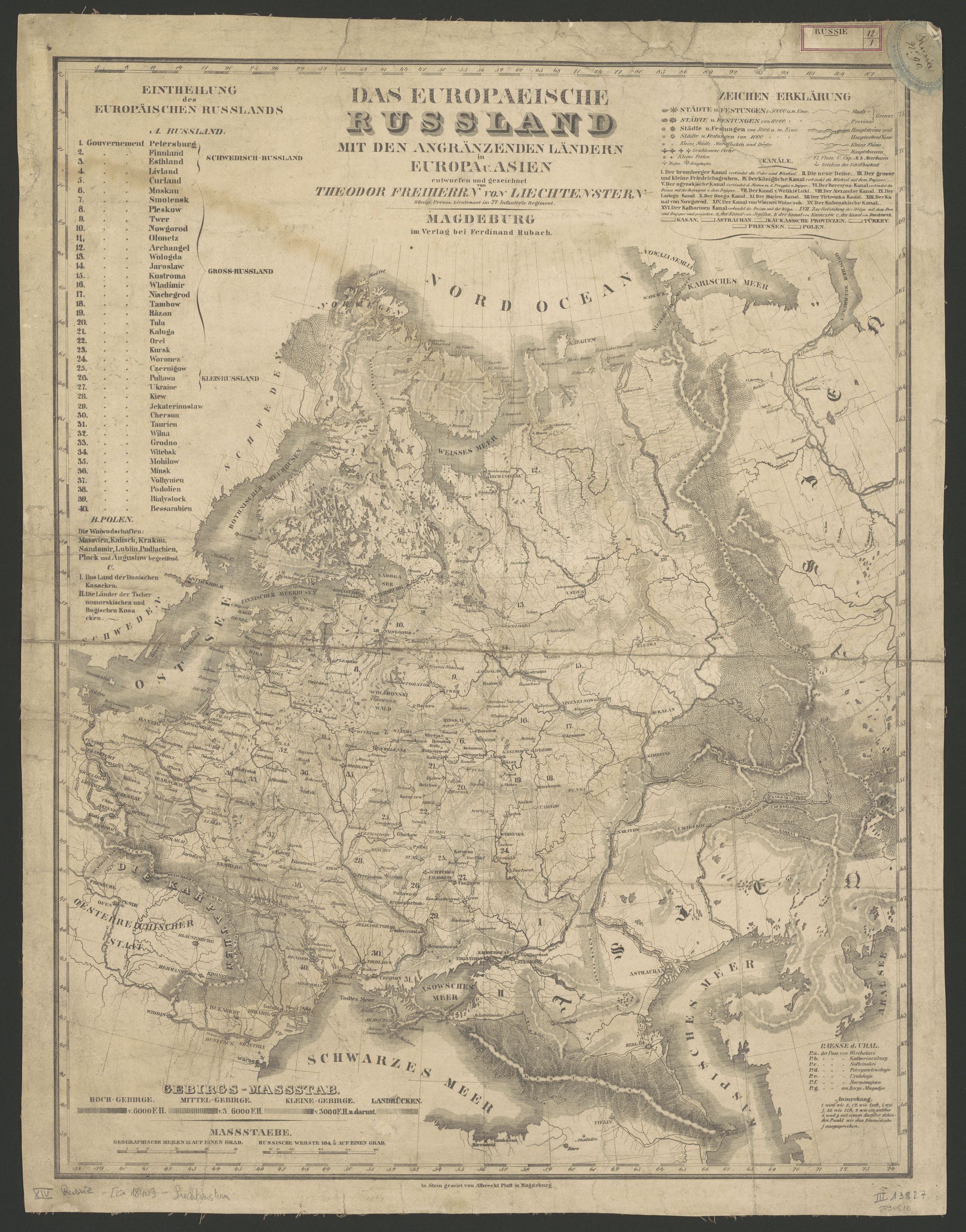

KBR, XIV Russie, XII Europe part. Sud Est - [1918] - Flemming - IV 3301

The map provides an overview of the languages spoken in the region around the Black Sea and indicates the new borders between the different countries in the region as they were decided by the signatories of the Treaty of Brest.

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed in the fortress of Brest-Litovsk on 3 March 1918, only a few months before WWI ended, by the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) on the one hand, and the Central Powers on the other hand (the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire). The signing of the treaty meant the end of Russia’s participation in WWI. Leon Trotski, who took part in the negotiations on behalf of the RSFSR, had been instructed by Vladimir Lenin to give in to all of Germany’s demands. Lenin preferred to end WWI as soon as possible and safeguard the socialist revolution.

Under the final terms of the treaty, the Soviet Republic gave up large pieces of land and funds to Germany. Henceforth, Germany would be protected by a chain of satellite states in the east: the Baltic states, Finland, Poland and Ukraine which had seceded from the RSFSR in late January 1918. With this treaty, Russia lost over one third of its population and agricultural land, half of its industrial companies and most of its coal mines. For Germany, the treaty meant the end of the two front war, and it enabled the Germans to launch their “Kaiserschlacht” against the western allies in the summer of 1918. When WWI had ended, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was annulled by the Treaty of Versailles (1919), but most of the new states who had emerged by the Treaty of 1918 remained viable independent states.

Julius Iwan Kettler (Osnabrück 1852- Berlin 1921), the map maker, was a statistician, geographer and cartographer. He was affiliated with the Geographisches Institut in Weimar in the 19th century. Besides this map, he made other war maps for the German publisher Flemming in Glogau (nowadays in Poland). His linguistic map of 1918 shows the linguistic and therefore cultural unity of the young republic of Ukraine.

Sources: https://earthworks.stanford.edu/catalog/stanford-th789jr0324; Walter Steiner, Uta Kühn-Stillmark, Friedrich Justin Bertuch: ein Leben im klassischen Weimar zwischen Kultur und Kommerz, Köln, Weimar, Böhlau Verlag, 2001.

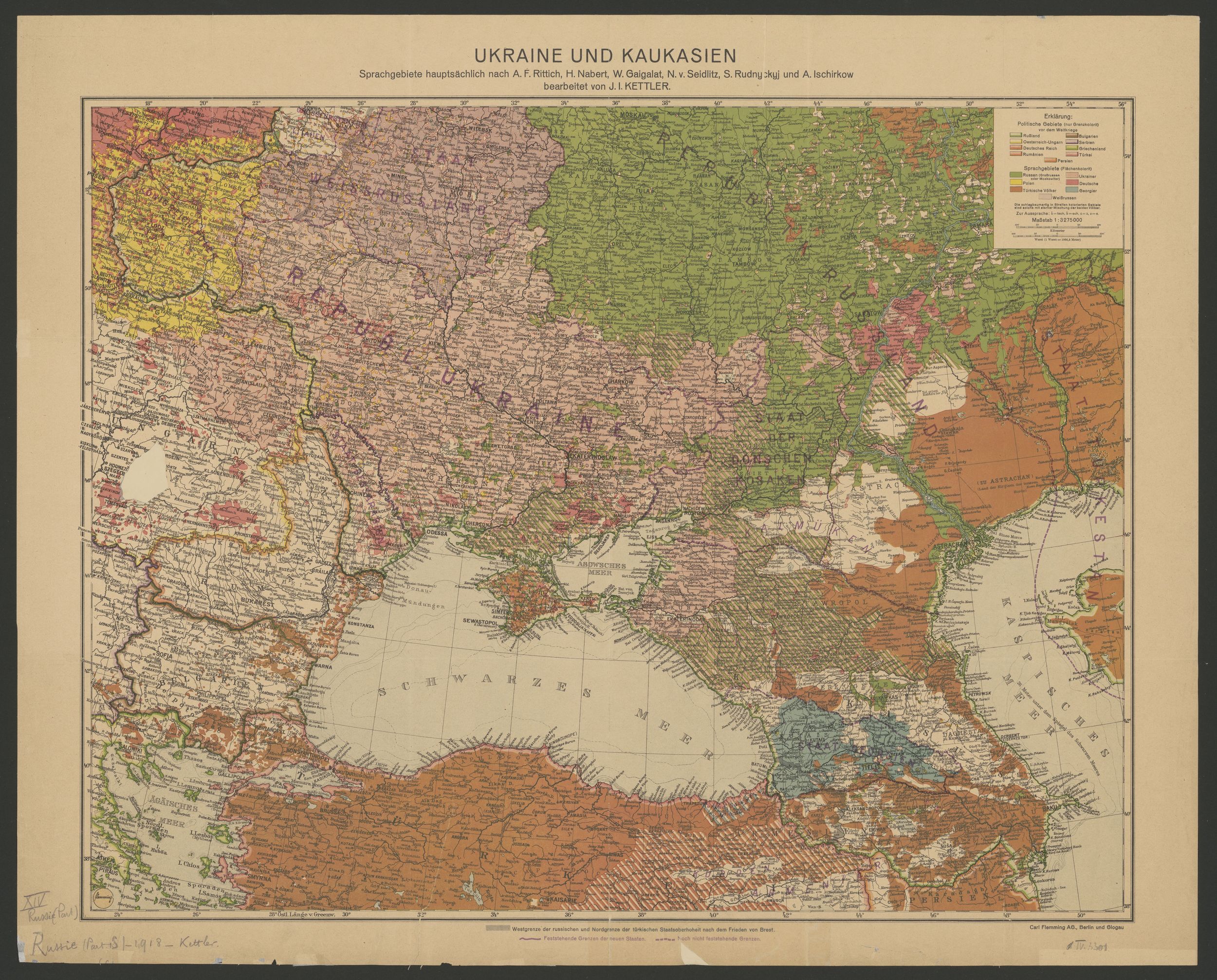

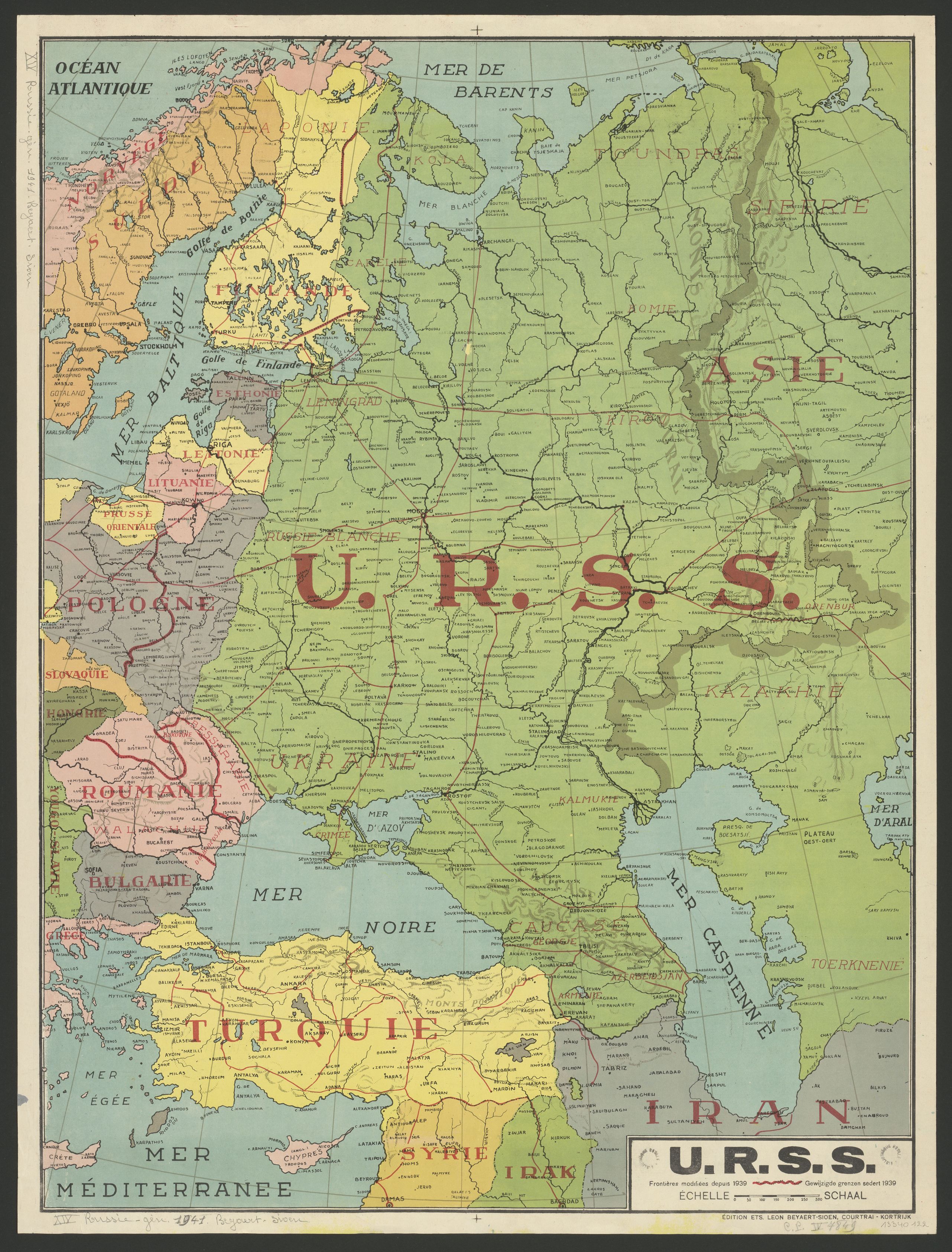

The Soviet Union I and II

KBR, CP IV 7857

KBR, CP IV 7849

Both maps of Russia were issued in Belgium in the same year. The first map was printed by the Brussels editing house De Rouck which is well known for its maps, the second was published by the printing house Beyaert-Sioen in Kortrijk. Although both maps date from the year 1941 they paint a very different picture of the then Soviet Union.

The Brussels map shows the many autonomous regions that were part of the Russian Union, like Ukraine and the Crimean Republic. The autonomous Crimean Socialist Soviet Republic was founded as early as 1921. In 1945 it was annexed as an oblast or province to the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, and thus to the Soviet Union, until the year 1954, when it was transferred to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. This Ukrainian Republic dated back to 1922 but only became an independent state in 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union. In this period, the Republic did have a certain independence with regard to its international politics.

The Kortrijk map highlights by means of its colouring the political union within the USSR or Soviet Union. The solid black line separates European Russia from Asian Russia. A red line situated in Poland and Romania indicates to where the Russian troops had advanced in 1941. Russia had invaded Poland in 1939 in the context of the so-called Molotov-Ribbentropp Pact, the treaty of non-aggression between Nazi Germany and Russia that was signed in August of the same year. This Pact authorized both countries to invade Poland, Germany from the west and Russia from the east, and to annex it. Then, in the summer of 1940, Russia occupied Bessarabia and North-Bukovina. North-Bukovina is nowadays a part of Ukraine. Southern Bessarabia is also Ukrainian today and makes up the province of Odessa. It was part of the Budjak region and was Ottoman until 1812. In the second half of the 19th century it became for a while a part of Moldavia and of Romania, then it became Russian again with the remainder of Bessarabia. In 1917, the whole of Bessarabia became a part of Romania, until the year 1940.

Sources: https://www.beyaertprinting.be; G. Cioranescu, Bessarabia : disputed land between east and west, Bucuresti, Editura fundatiei culturale romane, 1993.